As a kid I eyed Labor Day with a mix of anticipation and dread. On one hand, it most assuredly meant a gathering at the house. Steaks on the barbecue, corn on the cob, family, friends, badminton, croquet. On the other, it signaled the end of summer and the start of yet another school year. I was eight that year, and had recently begun counting on my fingers the number of years I had left in the public school system. So yes, I had mixed feelings on that summer weekend.

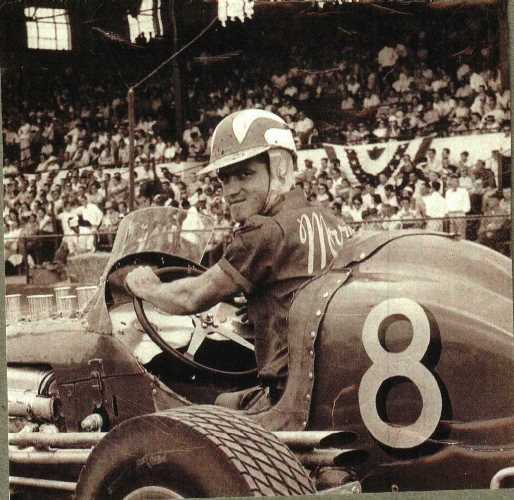

But that Labor Day promised there would be even more cause to celebrate than the usual backyard gathering. There would be that, too, but first my parents had an outing planned. In his younger days, prior to being drafted to fight in Korea, my dad, aka: Toby, had been a race car driver. And that weekend, Bert Brooks, one of his old racing buddies, was coming to Hershey Stadium to race midgets. After the race, Mom and Dad expected he’d take them up on an invitation to come home for steaks on the grill.

I may have not personally known Bert Brooks — who I never thought of as Bert or Brooks, but always as both — but I knew a race car driver, a premier driver at that, in your own backyard clearly qualified for certain bragging rights, and I, one of the only girls in my neighborhood, was not shy about spreading the news.

“Bert Brooks the race car driver is coming to my house after the race for a barbecue,” I boasted to the first two neighbor boys I encountered. They stared at me for a second, absorbing my news with barely disguised awe, then resumed being boys.

“So what,” Bobby said.

“Yeah, so what,” echoed Bobby #2. “Big deal.”

But I knew better. This was big.

We headed to the race early so Toby would have time to visit with his friend in the pits, wish him luck and make sure he knew we had a steak with his name on it. Mom and I found our seats with Aunt Ethel and Uncle Frank, who were not actual relatives, but the rich, old New Jersey antique car collectors who sponsored my dad in his racing days. A few minutes later, Toby returned to us. He had been too late to get into the pits, but he would talk to Bert after the race.

The Hershey 100 was an annual tradition and the stadium was packed with 20,000 spectators. The sky was a sort of a ho-hum gray, but not really threatening rain. The drivers lined up, the flag went down and off they went around the dirt oval track. I don’t know how many laps they were into the race when the yellow caution flag came out. Bert Brooks slowed to allow another driver to enter the pit, but the drivers behind him must not have seen the flag. Two cars slammed into Bert Brooks. His open cockpit midget stood up on end, balanced for a moment, then fell, landing — as my eight-year-old brain processed it — on Bert Brooks’ head. As one, the crowd gasped and as one, we fell silent.

“Oh Toby,” my mom said.

“I know,” my dad said, standing, hands on his hips, staring across that gray divide. We watched until the ambulance carried Bert Brooks away, then the drivers took their places on the track and the race resumed. But now the stadium was quiet, the drivers merely going through the paces.

My mom turned to my dad, “They’re not even racing. It’s like they’re playing follow the leader.”

My dad just nodded, his tanned face etched with worry.

It wasn’t long after that the loud speaker crackled. At 48, Bert Brooks was dead. They halted the race. We had a moment of silence, and we all went home.

It took me many years, decades even, to understand the impact of that day just before the start of third grade, the impact of seeing someone who I had expected to join us in our back yard, maybe even take a walk around the neighborhood with me, die.

My Labor Days since have been tragedy-free, but Bert Brooks has remained by side, a grim reminder that the bells do eventually toll for us all.

Lori Tobias covered the coast for The Oregonian for nine years. She lives in Newport, where she freelances for a number of regional and national publications. Follow her at loritobias.com.

Comments are closed.